There’s a photo of another version of me that resurfaces every once in a while, materializing unbidden from my digital unconscious. I’m 15, and deep in the throes of my MySpace era. Thick kohl eyeliner curls beneath my eyes into dramatic, feline points as I peer upwards from beneath a blunt fringe, and my pout is twisted to one side in a facial expression that died when the scene did. I’m wearing an age 10 Spider-Man T-shirt I’d picked up from H&M that weekend.

Snapped in 2006 on a compact digital camera, it was initially uploaded to MySpace as an offering to the gods of validation. Later, it would make the rounds on Facebook and Instagram Stories as nostalgic evidence of my digital tenure. Today, it exists ambiently in my iCloud and social media history, served up intermittently by algorithms designed to farm my engagement by baiting me with fuzzy memories of a younger self. It’s been uploaded, downloaded and reuploaded so many times that the time stamps are almost always incorrect. The metadata rewrites my chronology, my personal temporality untethered. Was I 15 in 2011? Or 2014?

I’ve evolved plenty since she was calling the shots in our shared vessel of flesh. But perhaps the reason my memory of her is so potent, is that she was the first version of me that I consciously created. The emergence of MySpace – and Scene as a subculture – catalyzed my earliest experimentation with what it meant to create another me: one that was prettier, cooler and more interesting than the one who had to go to school, deal with puberty, or live with my mother. MySpace set me free from myself, exposing me to a constellation of infinite alternative timelines.

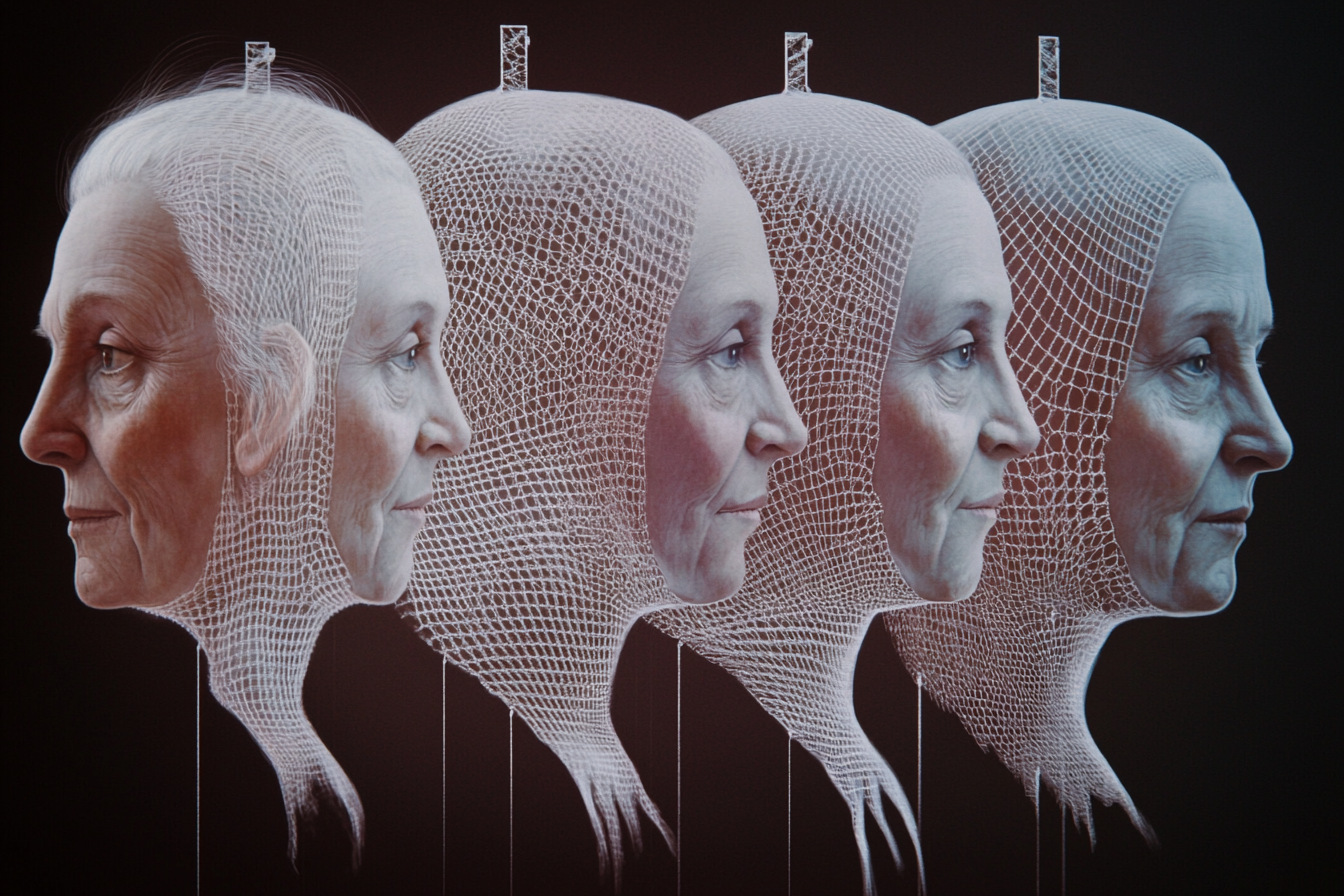

Early blueprints from my egostack

Early blueprints from my egostackConfronting contradiction

When we’re little, we’re fed the myth that as we get older, our sense of self will solidify. But it might be more accurate to say that getting older means getting comfortable with the contradictions of who you are, who you’ve been, and the many iterations you might become.

As adults, we realize that many selves exist simultaneously, programs that run quietly in the background. Our earthly forms toggle between them in response to the social context: work, home, Instagram, Reddit, dinners with friends, bars with strangers, coffees with acquaintances, etc. With every new or unfamiliar context, our parameters are adjusted so a more compatible iteration can be created and deployed. “Do I contradict myself?,” Walt Whitman once asked. “Very well then I contradict myself (I am large, I contain multitudes).” Whitman’s self-acceptance and nonchalance is enviable – I personally find the experience of being confronted with my own contradictions to be mortifying.

This aspect of the human condition – and the specific flavor of existential angst that’s attached to it, for some – is reflected in the resurgence of the doppelgänger. And nowhere is it more explicitly highlighted than in Severance, where workers at a mysterious (and definitely evil) company named Lumon willingly undergo a procedure to sever their lived experience into two parts, dictated by geography. The moment they enter the office, they become their ‘innie’, who has no episodic memory (relating to their own personal experience), but is otherwise fully functioning. When they leave, their ‘outie’ regains control of their shared body, able to live life free from the horrors of work, while their innie exclusively experiences the 40-hour work week they spend at the office.

On the surface, this is a comment on modern white collar labor, and a satire of the sanitized, media-trained iteration of ourselves reserved for professional contexts. But its premise serves as a useful vehicle for not only exploring the ways in which we contort ourselves for different contexts, but for unpacking what exactly it is that makes us who we are – nature, nurture or something bigger.

The year of the doppelgänger as a manifestation of late capitalism (via @longtosee)

The year of the doppelgänger as a manifestation of late capitalism (via @longtosee)The commercialized self

For as long as social hierarchies have existed, there’s been a purpose for multiple iterations of who we are. Erving Goffman’s self-presentation theory – which repositioned selfhood as a social performance in popular science – dates back to 1956. But code switching was once an ambient part of what it meant to be a person in the world. Now, not only are we playing an ever-expanding cast of characters, but we’re expected to commercialize them for public use, before facing their contradictions head on in the panopticon of our digital ecosystems.

The Substance explores the implications of multiple, deeply contradictory versions of who we are being forced to co-exist: public and private, filtered and unfiltered. TV fitness guru Elisabeth Sparkle is told she’ll be fired on her 50th birthday, leading her to experiment with a black market substance that promises to unlock “a better version of yourself,” but predictably reveals itself as more of a Monkey’s Paw situation. What transpires is a grotesque body horror that oscillates between sublime beauty and aberrant gore, exploring the self-directed disgust that can transpire from such aggressive forms of performance.

The internal battle between Elisabeth and her double Sue, crescendos in a B movie-esque wrestling match between these two parts of a whole. Sue, having drained Elisabeth of her strength, self-worth and spinal fluid (yes, seriously), is a cartoonishly powerful figure, an Amazonian princess clad in a silky pastel singlet standing over the weakened and deformed Elisabeth. She gazes over her with disgust, embarrassed to even acknowledge that this deformed creature is part of her own making, before smashing Elisabeth’s withered face through the shattering shards of a mirror. This metaphor for the deep self-loathing that so many people feel is a timely commentary on the parts of ourselves we – and especially women – scythe off and hide away in the name of our public personas, regardless of the negative implications for long-term happiness.

The Substance, 2024

The Substance, 2024The grammar of selfhood

There’s a chance that this contradiction is felt more deeply in some cultures than others – a truism that’s reflected in the language of the self. In English, temporary states and permanent attributes are both addressed by the singular "I am," creating a static container for selfhood — one that perhaps makes our present day identity fragmentation feel more jarring, more contradictory.

But that’s not the case for many other languages. In Portuguese (and most Romance languages), there are distinct verbal constructions for temporary feelings versus permanent states. The distinction between “estou feliz" (“I am happy right now”) and "sou feliz" (“I am a happy person”) creates a profound boundary between the ephemeral and the essential – a linguistic architecture that is hardcoded with the multifaceted nature of the self.

Japanese is also laced with the nuance and complexity of social identity. The concept of ‘tatemae’ (public behavior) versus ‘honne’ (true feelings) explicitly acknowledges the social masks people wear, while a spectrum of first-person pronouns shift according to social position, formality, and relationship. These pronouns aren’t just related to concrete identity markers, but entire modes of self-presentation that imply a range of social implications and relationship dynamics.

These linguistic structures have long found expression in the context of mediations on identity. In the 2003 movie Doppelgänger, protagonist Hayasaki initially uses the standard, composed ‘watashi’ (another word for ‘I’) when referring to himself. When his doppelgänger appears – physically identical but temperamentally more aggressive – he adopts the more assertive ‘ore’, which typically evokes a rougher impression of masculinity.

While English has a tendency to imply permanence and singularity in selfhood, languages that grammatically distinguish between temporary and permanent states may offer a built-in framework for reconciling the egostack. The horror of confronting your contradictory selves – Elisabeth facing Sue in their final showdown, or innie Mark S coming face-to-face with the life of his outie – might carry different emotional textures when your primary language already houses multiplicity within its grammar.

Doppelgänger, 2003

Doppelgänger, 2003Overwriting outdated scripts

Digital media hailed in an epoch where people were able to break out of the roles they’re expected to perform, and write a whole new script. In Glitch Feminism, Legacy Russell discusses the internet as a means of recreating yourself in your own image, rather than the image dictated by dominant forces:

“We want a new framework and for this framework, we want new skin. The digital world provides a potential space where this can play out. Through the digital, we make new worlds and dare to modify our own. Through the digital, the body 'in glitch' finds its genesis. Embracing the glitch is therefore a participatory action that challenges the status quo. It creates a homeland for those traversing the complex channels of gender's diaspora. The glitch is for those selves joyfully immersed in the in-between, those who have traveled away from their assigned site of gendered origin. The ongoing presence of the glitch generates a welcome and protected space in which to ... experiment. Glitch feminism demands an occupation of the digital as a means of world-building.”Today, identity expression isn’t just performed through the act of contributing to digital media, but consuming it, too. The algorithm has become so fundamental to identity formation that a recent qualitative study of 13- to 17-year-olds in the US found that participants felt their 'For You' page on TikTok wasn't just for them but about them – a mirror in which they can curate and observe the many facets of their whole. It’s a shift that’s rewired the way many people think about the self in the context of wider culture – longitudinal studies and headlines in marketing press abound pointing to the fluid identities of the first generations to be truly digitally native.

But the diversification of who we can be, and how we can communicate it, isn’t just reserved for the young as they shapeshift their way towards adulthood. It’s a reality all of us now face: a reality that creates both liberation and exhaustion. Social psychologists Creary and Gordon discuss "role conflict" and "role overload" in their research — the cognitive dissonance that emerges when competing versions of self demand simultaneous performance, and the overwhelm that ensues. "Conflict occurs because the performance of one role interferes with the performance of another," they explain in their paper ‘Role Conflict, Role Overload, and Role Strain’.

The models we associate with these roles haven't been rewritten so much as overwritten. The ghostly presence of older templates remain beneath contemporary expectations: the professional woman navigates not just workplace competence but historical stereotypes about feminine assertiveness. Those who are childless-by-choice navigate not just personal fulfillment, but persistent social narratives that frame reproduction as the ultimate validation of adulthood. These ingrained perceptions die hard, creating a feedback loop of constant internal conflict.

The egostack, created with Midjourney

The egostack, created with MidjourneyThe egostack as survival

In nature, duplication and mimicry is an indication of evolutionary brilliance. The viceroy butterfly doesn't corrupt itself by mimicking the monarch's warning patterns – it ensures its survival through strategic adaptation. Elisabeth's creation of Sue follows this same biological imperative: in a culture that renders aging women invisible, her mimicry of youth becomes necessary armor against obsolescence.

Conversely, aggressive mimicry sees the predator mimic the prey for its own gains. When Helena cosplays as Helly R throughout Severance's second season, she deploys this type of mimicry – adopting the appearance and behaviors of her severed self to navigate the deep isolation of her unsevered existence. Her performance isn't deception but adaptation to hostile terrain, a necessary strategy for psychological survival.

Is it a reach to say that our own tendency towards duplication is any different? The widespread adoption of social and digital platforms may have given us the tools to rewrite the rules of personhood, but the backdrop of economic and political uncertainty was what gave us the fire to challenge the status quo.

We've been forced to evolve; the roles we've been required to play expanding exponentially. In the US, working mothers recently reached record highs, while more than half (52%) of millennials in the US work some type of side hustle alongside their day job. Meanwhile, outside of work, a growing number of people are seeking meaning and fulfillment through hobbies and community activities that connect them to their interests or locales – a rising behavior that correlates with the proliferation of the loneliness epidemic.

With this in mind, maybe the weight that we place on coherent selfhood deserves some reframing. If our multiplying selves are not a compromise of our integrity, but an evolutionary necessity, could we reconcile our expanding egostack with the need for coherence? Seeing other versions of ourselves may not always feel good, but there's a quiet redemption in embracing our contradictions – not as failures of authenticity, but as evidence of our capacity for diversity and growth in the face of all the odds.

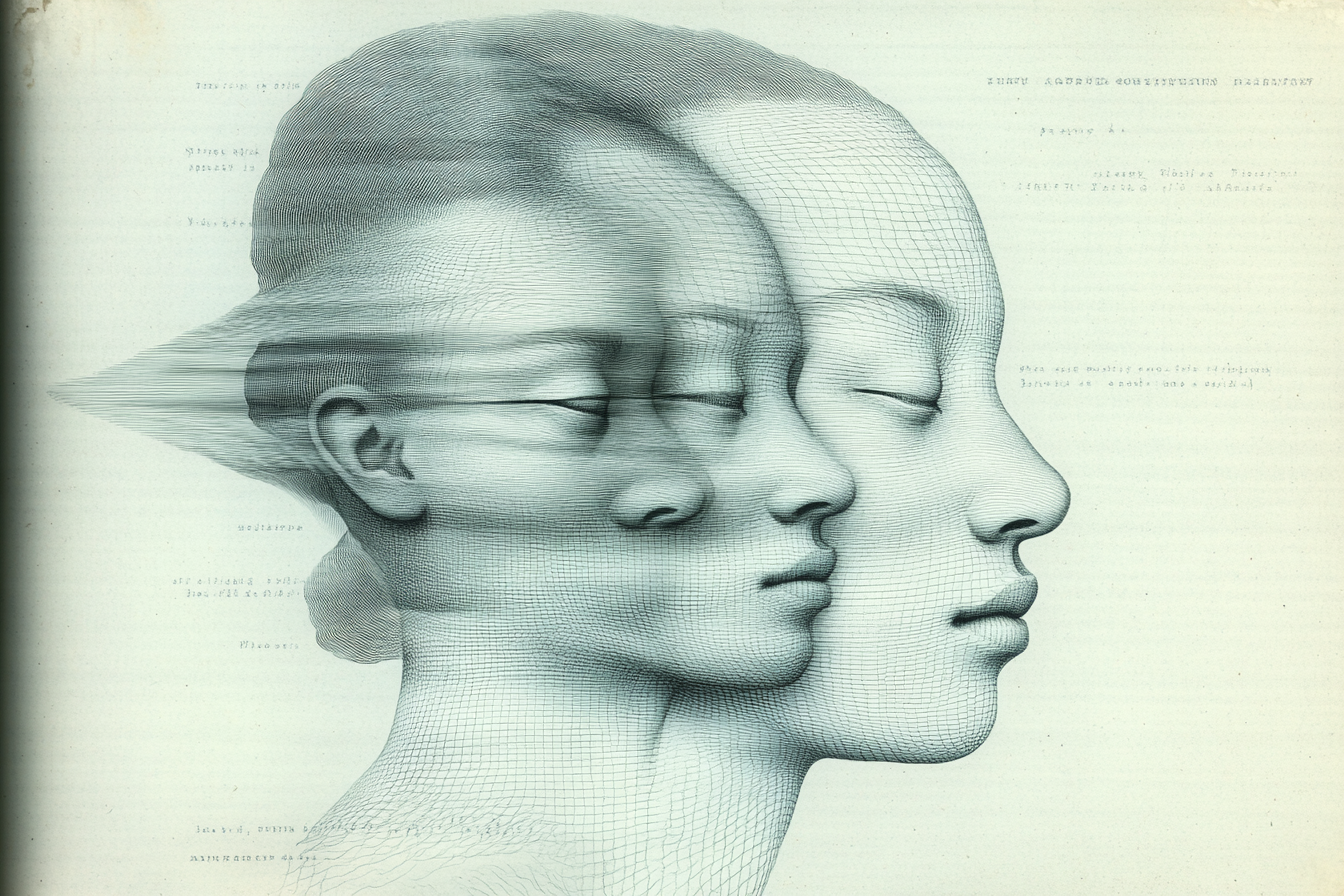

Mimesis by Seb Janiak

Mimesis by Seb JaniakThe future of the ego stack

We’re going to need to get on board. If digital media has proven itself to function as an existential photocopier – with each of us as the source material – the next generation of AI-enabled tools promises even more rapid and radical replications of selfhood.

One of the earliest examples of the mass adoption of generative AI tools took the form of viral AI-selfie generators like Lensa AI, which took off in late 2022. These Trojan horses for data mining enabled us to print infinite iterations of ourselves as forest fairies and retro-futuristic robots – with some very problematic outputs. Since then, the behavior of generating stylized images of yourself with the help of AI has become standard practice, IP rights and the proliferation of harmful stereotypes be damned. Apple has developed a dedicated app for this exact purpose – Image Playground – which draws from the years of photos in your iCloud, while a cottage industry of glorified selfie generators has formed around use cases like getting the perfect professional headshot or trying on clothes before you buy them.

Doji, one example of the latter, requests several selfies, and the input of height and weight, in exchange for the promise of accurate portrayals of garments when worn. Applying the user’s face to a virtual mannequin that boasts the lithe frame and aspirational bone structure of a model from luxury fashion retailer SSENSE, the end result is far from reflective of what the clothes would actually look like; the dimensions entered are rendered redundant. Instead, the user receives a one-way ticket into an uncanny valley of facial and body dysmorphia. None of these versions are the real me. But could they be? New unrealistic expectation unlocked.

As we dive face-first into a future of infinite selves, the algorithms that serve up our earlier versions seem less sinister. When MySpace Lore springs into view, she may be disorienting, but she’s also part of my personal archives. She’s an artifact of who I once was, and a reminder that selfhood has always been an iterative process – one in which I have always had agency to evolve on my terms. In this sense, there are parts of her that are still alive – and at least I know those parts are definitely real. In a not too distant future, that might be a luxury I’ll wish I hadn’t taken for granted.

Doji: an uncanny valley of me

Doji: an uncanny valley of me